The Mexican Connection

By Mary Agnes Welch

From Hog Watch Manitoba

2002

Migrant workers pack up their dreams and come to Manitoba to take jobs on farms and at Maple Leaf's pork-processing plant, but the rules that govern them are raising the hackles of labour leaders.

Roberto Rocha contemplated the job offer posted in a Mexican municipal office for six months before taking the plunge.

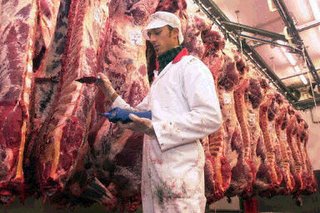

With one suitcase, the soft-spoken 20-year-old travelled from the industrial mega-city of Leon to Brandon for a coveted job at Maple Leaf's pork-processing plant.

"I came simply to work," said Rocha, a former employee of a Leon tannery. "The work I did in Mexico, I don't even want to think of it any more."

Now, after six weeks of English classes and on-the-job training, he's one of the fastest cutters on Maple Leaf's production line, and is teased for spending his wages on sharp new clothes, including a brown, '70s-style leather jacket.

There are more than 300 Mexican workers in Manitoba, most of whom toil on vegetable farms near Portage la Prairie as part of a decades-old government guest worker program. About 45 workers, though, are working in Brandon's state-of-the-art meat-processing plant, part of a controversial program that will expand fourfold next year. Another 200 Mexican workers are expected in 2003, as the company ramps up plans to add another shift to the plant, which now employs about 1,300 production workers.

The first wave of Mexican workers arrived in January. For every one hired, 25 applied to a recruitment office in Leon. Most say they would like to become Canadian citizens.

Unlike many new immigrants, the Mexican workers are not left to flail around on their own as they search for apartments, apply for health cards and set up bank accounts. The company offers intensive English classes, with more courses scheduled later at the union hall. Local Catholic churches, especially St. Augustine's, are opening their doors, and a Spanish-speaking Maple Leaf staffer acts as a liaison, helping the workers get settled and find their bearings in Brandon. Plus, a second wave of workers who arrived in August got advice and even a place to stay from those on the job since January.

But, labour leaders and aboriginal groups say the practice of importing labour from poor countries drags down wages and nixes a worker's right to sell his or her labour elsewhere. The temporary work visa -- one or two years -- allows its holder to work only for Maple Leaf, meaning they cannot go down the road and work for meat packer Springhill Farms in Neepawa, where wages are $2-$3 per hour more than at Maple Leaf.

That circumvents basic supply and demand forces between workers and employers, said Jan Chaboyer, Brandon Labour Council president. That could be fixed if the foreign workers were simply given landed immigrant status.

"We're just saying that if they're good enough to work here, they're good enough to live here," said Chaboyer. "If employers can set up shop anywhere in the world under globalization, then likewise workers should be able to move freely, too, to where the salaries are."

Maple Leaf's Steve LeBlanc said the company badly wants the Mexicans to immigrate and plans are in the works to have immigration papers in place once the temporary work permits expire. He said the company is also exploring Immigration Canada's new nomination program, which allows employers to sponsor skilled labour for waiting jobs.

Another criticism goes like this: If Maple Leaf can't attract workers, it should simply increase salaries, which are among the lowest for Canadian meat packers.

Leah Laplante, vice-president of the Manitoba Metis Federation-Southwest Region, says Maple Leaf's wages are simply too low to recruit workers.

"To move a family into Brandon for $8.65 an hour, you can't do it. You just can't do it," she said.

That wage works out to less than $18,000 per year. The MMF has also placed members in jobs with Maple Leaf.

Maple Leaf's human resources manager Steve LeBlanc maintains wages are not the only way to attract employees.

"Companies have to be careful. Just throwing money at the problem is not a solution," said LeBlanc. "We believe we're paying a very market-competitive rate. Many industries paying very competitive rates are still having a challenge finding employees."

When Maple Leaf announced it would build its $120-million plant in Brandon, well-paying jobs were anticipated. Meat packing has always been a hard job but what kept workers loyal in the past was a pretty good wage.

However, Maple Leaf slashed its wages by 40 per cent prior to opening in Brandon in 1999, dropping the starting salary down to just $8.65 today. It also enjoys a seven-year collective agreement it negotiated with the United Food and Commercial Workers -- one of Maple Leaf's demands before it agreed to open shop in Brandon. The contract doesn't expire until 2006.

"The challenge for us is Brandon is a fairly tight labour market. Unemployment is about three or four per cent," said LeBlanc of Maple Leaf.

Maple Leaf tried recruiting in the Maritimes, northwestern Manitoba and rural Saskatchewan and Alberta, with limited success, said LeBlanc. It then turned to the federal Human Resources Development Canada to find foreign labour.

The Mexican labour also addresses Maple Leaf's other concern: high staff turnover. Their work visas lock in the Mexican workers for one or two years, and they have far lower no-show rates than Canadian workers.

The Mexican workers who arrived in January all earned the six-month perfect attendance award which entitled them to a healthy bonus.

Another concern: When the new shift is up and running, the union fears Brandon's infrastructure, especially its housing stock, won't be able to handle an influx of about 800 workers, both Canadian and Mexican. But the union says it is talking with the provincial government, pushing it to start looking at improving housing, child care and other services.

Francisco Echeverria, who left behind a wife and two daughters in Leon, shrugs off the suggestion that the leap into life in Brandon was jarring.

"I was looking for another job, and I saw the ad in the newspaper and I think 'Canada? Why not?'" said Echeverria, who checked Brandon out on the Internet before coming. "I like the town atmosphere. You don't see violence. You can walk anywhere at three or four in the morning and nothing will happen."

Echeverria's English is strong, and he hopes to become a Canadian citizen, something Maple Leaf is lobbying the province and federal government for.

Meanwhile, on the province's vegetable farms near Portage la Prairie, the practice of importing Mexican workers has been in place for decades. It mirrors a similar practice in the tobacco fields and greenhouses of southern Ontario, where concerns have been raised about the migrants' access to decent housing, employment standards regulations and basic community services.

But labour and agriculture groups have raised no such concerns in Manitoba, and the men who spend six months at a time among the rows of cabbage, celery and carrots have a 70-per-cent return rate, said Darrell Fiel, the federal government's point man on the program in the region.

As part of a contract, employers must provide the Mexican migrants with workers' compensation coverage, decent housing, a portion of their travel expenses and laundry facilities.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home